It is a peculiar reality of humankind that a person can be supremely confident and yet entirely wrong. How many men have stood before a crowd and expressed “truths” with such confidence that the events of the day were swayed by mass agreement? A dictionary definition of confidence describes it as:

“certitude; assurance: He described the situation with such confidence that the audience believed him completely.”

Confidence can be a juggernaut that flattens opposition, in spite of the unlistened to whispers that the facts, the truths, or the ethics are pointed in the wrong direction.

It is especially in the fields of ethics and religion that confidence has produced results both magnificent and tragic. Humans want life to resonate with meaning – enough meaning to lift their souls above the dreary and monotonous reality of daily survival. It is thrilling to imagine that we can contribute to a larger and higher purpose that will save the day, or save the world. We don’t mind sacrificing for a cause that seems just.

It is thus that we can be trapped under the sway of the confidence of others. When we’re young, our own confidence can seem unbreakable. We may not realize that it might be the confidence of a barnacle riding on the back of a gray whale. In such cases, it is the whale that gives us direction.

My mother, Polly Kapteyn Brown, was a philosopher, a writer and an artist, and was my best friend growing up. We often had stimulating conversations about the meaning of things. At one point, in my crass youth, I tendered my opinion that a certain point was “the absolute truth.” I had amazing confidence. She looked at me and said, “You know there’s no such thing as absolute truth, right?”

My mother, Polly Kapteyn Brown, was a philosopher, a writer and an artist, and was my best friend growing up. We often had stimulating conversations about the meaning of things. At one point, in my crass youth, I tendered my opinion that a certain point was “the absolute truth.” I had amazing confidence. She looked at me and said, “You know there’s no such thing as absolute truth, right?”

Indignant at the notion, I replied, “Well, Mummy, you seem rather absolute about that.”

That conversation did not reach a conclusion. But later, as I traveled from Maine, to New York, to Washington, DC and West Virginia, and then on to California, Las Vegas, the Southeast, and diverse places in between, I met a multitude of very confident individuals who were completely convinced that their view of life was correct. It was curious, since many of their views were contradictory.

Religion was a frequent topic of conversation, and I was asked more than once, “Are you saved?” Visiting Southern churches in South Carolina and Virginia stimulated vigorous conversations about chapter and verse, and even more importantly, which version of the Bible was being referenced. I never knew until I reached the South that King James had so much authority. My positions were less than defensible, since I had purchased an elegant, leather bound edition of The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha, Revised Standard Version. The Apocrypha? “Lord have mercy!” as they murmur in the South.

I left home when I was just nineteen. Now, after forty years of exploring religion, spirituality and politics, I am back in my hometown of Portland, Maine, consorting with artists, musicians, aging hippies and other liberal types that would make Southerners blanch. I’m a centrist conservative, but I try to get along with just about everybody. I was a teenage hippie, after all.

The phenomenon of Confidence has not changed. Having both conservative and liberal friends, it is fascinating to observe the levels of confidence that are expressed in group settings of like-minded individuals. Controversial topics produce polemics from both sides that scorch the opposition roundly, all stated with aplomb and conviction.

For many of those forty years of religious exploration, I also had a barnacle-like conviction, riding the gray whales who spoke with more authority than I. As time passed, as I stumbled through the decades, I began to understand that I didn’t know everything. As the 18th century English poet, William Cowper, wrote, in Winter Walk at Noon, “Knowledge is proud that he has learned so much; Wisdom is humble that he knows no more.”

I met many alpha males and alpha females in my studies to become a “leader.” Some were humble and lovely and warmed my heart. Others, with complete and utter confidence, followed the tradition of “tough love,” and used scolding as a motivator. Having experienced both methodologies, I now agree with Cowper, when he wrote, “I believe no man was ever scolded out of his sins.”

In the last ten years, I’ve devoted much of my free time to reading a large variety of books about spirituality and mysticism. I’m especially fond of the Christian mystics of the High and Late Middle Ages; people like Mechthild of Magdeburg, Meister Eckhart, Julian of Norwich and Jakob Böhme, among many others. I find their writings deeply refreshing; a view of life that transcends doctrine and narrow theological infighting.

They also had confidence, but I felt that their confidence was more than just confidence in doctrine, but was instead rooted in the basic, experiential virtues of human life. Certain attributes of life are shared by all humans, whatever their opinions about religion and politics.

Are not all humans born as babies who yearn for motherly love? Children want to be hugged. Adults do too, if they dare to remember what hugs felt like. Adults are universally attracted to love, and thrive when they live – and work – in an environment of kindness and compassionate love. Yes, pain often causes the hearts of adults to atrophy and warp in tragic ways. Yet, just as a dying flower reaches for water as it struggles to stay alive, humans of every culture are instinctively attracted to the water of love. Love and compassion transcend culture and religion, and even no religion at all.

The twentieth century American philosopher and avowed atheist, Eric Hoffer, wrote, “Compassion is the antitoxin of the soul: where there is compassion even the most poisonous impulses remain relatively harmless.”

I find it quite pertinent that love and compassion are so universally acknowledged as virtues. Universal virtues are both the foundation of morality and the fruit of moral action. They act as guideposts in a world that is overwhelmed with information and a plethora of diverse opinions about everything.

In my own mystical search, I was asked how I could determine if it was God’s voice whispering in my heart and thoughts and soul. What if it was the devil, or a satanic angel, masquerading as God? It was a fair question, since more than one homicide bomber has claimed that it was God’s voice that urged him to kill and maim the innocent.

In the same vein, one might ask how anyone can decide to believe in any particular doctrine. How can one know what is true? How can we be truly confident in our brand of “truth?”

I always come back to a verse in St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, in verses 5:22-23:

“But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control.”

A pernicious doctrine will produce pernicious results. If someone hears words of violence or oppression in their prayers, or from religious leaders, the best test in the world is to compare them to the fruits of the spirit. Are the words kind and compassionate and loving? If they are not, then most assuredly they will produce harm if they are followed.

When someone says that the ends justify the means, they are ignoring the law of cause and effect. Harming others for short-term results will produce harm tenfold, as the harmful actions ripple out across the world. It makes much more sense to acknowledge that the means to the end are the same as the end.

Whether one believes that the virtues of kindness and compassionate love find their source in God, or simply are useful behaviors that everyone likes, it is a common experience among humans that love has a magnetic pull – a pull that multiplies as love is expressed. The more we experience loving kindness, the more we are attracted to it, and yearn to both receive it and give it.

Scientists state that everything is energy. Although they have not deciphered the energies of kindness and compassionate love, I believe that they are living energies with their ultimate source in a God who is far more affectionate toward humans than we have previously imagined. I am convinced that the beauty of nature and the goodness that we can find in our human experience demonstrate that God is passionately in love with all of us.

Ursula K. Le Guin stated, in her National Book Award Acceptance Speech in 1973, “For, after all, as great scientists have said and as all children know, it is above all by the imagination that we achieve perception, and compassion, and hope.”

Imagination lifts us out of the mud puddles of blind despair and allows our souls to fly away from every type of hell – and there are many. I find my imagination soaring when I see the sky, or trees, or birds and animals. If we really, truly look at animals, and regard them with the love that they deserve, we’ll sense something stirring in us; a resonance with the loving energy of the universe. For some, loving animals might be the very first step away from hell, and a life dominated by coldness or cruelty.

Imagination lifts us out of the mud puddles of blind despair and allows our souls to fly away from every type of hell – and there are many. I find my imagination soaring when I see the sky, or trees, or birds and animals. If we really, truly look at animals, and regard them with the love that they deserve, we’ll sense something stirring in us; a resonance with the loving energy of the universe. For some, loving animals might be the very first step away from hell, and a life dominated by coldness or cruelty.

St. Francis of Assisi wrote, “If you have men who will exclude any of God's creatures from the shelter of compassion and pity, you will have men who deal likewise with their fellow men.”

My wife, Kimmy Sophia, loves animals with her entire being. Now, with the Internet bringing news of animal abuse from around the world, it is often more than she can bear. How can men and women be so cold toward animals? Then one realizes that they are often just as cold toward other people, treating others as coldly as they themselves may have been treated. It seems to be an insurmountable task to engender change in the world.

But imagination breeds hope, and a glimmer that a force larger than humans is influencing the world for good. As William Cowper wrote, “Man may dismiss compassion from his heart, but God will never.”

My wife and I love watching British period films; among them, Agatha Christie’s stories about Hercule Poirot. In the David Suchet film version of Appointment with Death, Poirot gives advice to a young lady who has suffered multiple tragedies:

“There is nothing in the world so damaged that it cannot be repaired by the hand of Almighty God. I encourage you to know this, because without this certainty, we should all of us be mad.”

After forty years of religious exploration, I found myself sitting at the window of a hotel in Old Quebec City, on the morning of October 8, 2013. With Kimmy Sophia quietly sitting by, I lit a candle on the windowsill and gazed out over a park and the Saint Lawrence River. It was a commemoration of the forty years since I had left home at the age of nineteen. That morning, at fifty-nine, I decided that my next forty years would be a life spent focused on harmony and resonance with a God who I believe is far more interested in the virtues of kindness and compassionate love than with divisive doctrines.

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, wrote in Ethics for the New Millennium:

“Thus we can reject everything else: religion, ideology, all received wisdom. But we cannot escape the necessity of love and compassion.

This, then, is my true religion, my simple faith. In this sense, there is no need for temple or church, for mosque or synagogue, no need for complicated philosophy, doctrine, or dogma. Our own heart, our own mind, is the temple. The doctrine is compassion. Love for others and respect for their rights and dignity, no matter who or what they are: ultimately these are all we need. So long as we practice these in our daily lives, then no matter if we are learned or unlearned, whether we believe in Buddha or God, or follow some other religion or none at all, as long as we have compassion for others and conduct ourselves with restraint out of a sense of responsibility, there is no doubt we will be happy.”

I am confident that I know very little. At age fifty-nine, I have just entered the first grade of a school that I will attend for a very long time. That is tremendously exciting to me – that we can learn so much more than we now know.

Some religious individuals might think that I am doomed. I cannot effectively argue about doctrine with anyone, mostly because I believe that it is pointless. When you get right down to it, most doctrinal arguments are just expressions of belief and opinion based on faith. I don’t reject all doctrines. I simply believe that there is a deeper and more powerful way to journey forward.

I prefer to set my moral compass to the North Star of God’s kind and compassionate love, and just go for it, with confidence in the love and beauty that will multiply as I follow a compass that is alive with energy flowing from the source of life.

~ photo of Grace Brown with a Lamb named Kazoo ~

~ photo by James Freeman, used with permission ~

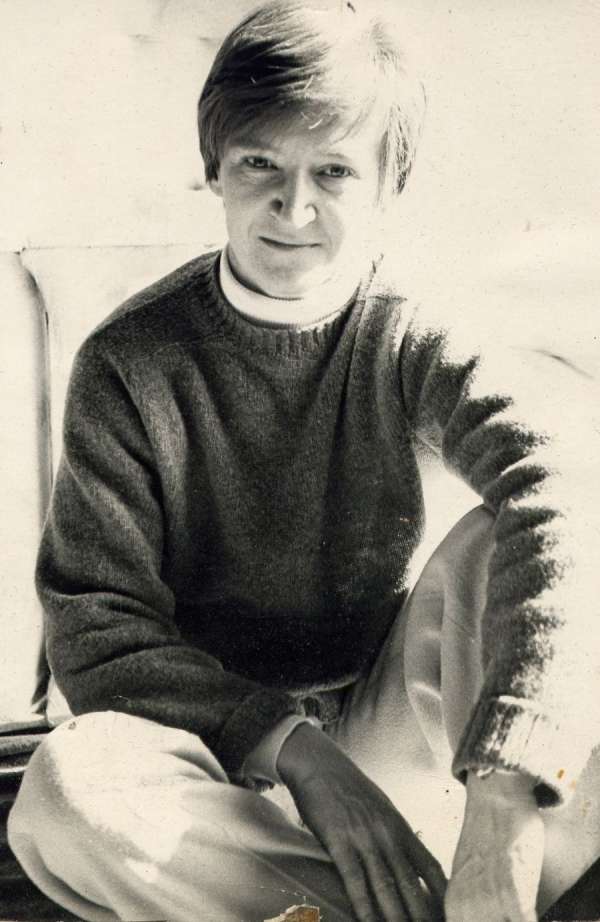

~ photo of Polly Kapteyn Brown ~

~ photographer unknown ~

Peter Falkenberg Brown is passionate about writing, publishing, public speaking and film. He hopes that someday he can live up to one of his favorite mottos: “Expressing God’s kind and compassionate love in all directions, every second of every day, creates an infinitely expanding sphere of heart.”

~ Deus est auctor amoris et decoris. ~