Reparations for Slavery? Everyone Has Slaves in Their Lineage Apr 4, 2022  Many in the Democratic Party are calling for reparations for slavery. Their arguments are countered by both black and white conservative leaders who contend that reparations are not practical and are, in fact, impossible to adjudicate fairly. My belief is this:

Let’s review the history of resentment and pain. It’s not as simple as it may seem. Here’s a challenge: pick up almost any history book that has true scholarly accuracy and start reading. I think it’s quite reasonable to say that history is a book in which virtually every page is drenched with suffering and blood. History is not a fun read. If one goes back far enough, it’s a pretty safe bet that every person in the world has ancestors who were killed, raped, enslaved, tortured, beheaded, and persecuted because of their race, religion, nationality, political views, or other factors. It’s also a safe bet that every person in the world has ancestors who committed the above misdeeds. At least one and probably many. Blacks were enslaved. Asians were enslaved. Hispanics and Indigenous peoples were enslaved. Whites were enslaved, too, by other whites and by other races as well. Slavery was the norm for most of human history and is still practiced today by criminal human traffickers and in countries like the Islamic Republic of Mauritania. Every race was victimized. Every race included victimizers. How then should the human race proceed to dissolve the historical pains of racism, slavery, and murder? We could discuss reparations, but shouldn’t reparations be truthful and accurate? Who is guilty? If a living person today has never harmed a person from another race or religion, are they responsible for the crimes of their ancestors? If so, which ancestors? How far does the investigation go back? Five thousand years? A million years? Is this a global process in which every country has to take stock, or does this only apply to America? Will a white person in America who immigrated after slavery ended be held responsible for the crime of black American slavery if his or her ancestors had nothing to do with it? Reparations for American slavery have already been offered on a massive scale by the 320,000 white Union soldiers who died in the Civil War (joined by 40,000 black Union soldiers), a sacrifice that freed the slaves only seventy-seven years after the ratification of the US Constitution. Most of those white soldiers had probably never owned or even seen a slave. Yes, they fought to preserve the Union, but many fought with the conviction that slavery was evil. Were their deaths meaningless, or were they instead the highest reparation that a person could give? If their deaths did not adequately pay reparations for the sin of slavery, how many deaths will it take? How much money will it take? Are forgiveness and reconciliation even on the tables of social justice warriors who seem to be driven by hate much more than by love? What about the descendants of those fallen Union soldiers? Are they exempt from additional reparations? If not, why not? The United States as a whole has demonstrated—with the sacrificial blood of hundreds of thousands of white men—that as a country, it has grown and matured and does indeed honor all people as sacred individuals. The sacrifices of the Civil War were finally fulfilled a hundred years later with the arrival of full civil rights, and race relations have continued to dramatically improve since the 1960s. What about African blacks who have African ancestors who sold their neighbors into slavery? Are they guilty of supporting slavery even though they didn’t do it themselves? Vice President Kamala Harris, a black Democrat, is a textbook example of why reparations for slavery cannot be accurate, fair, or sustainable. She’s a strong proponent of reparations, but according to her father, Donald J. Harris, her Irish ancestor was a slave owner named Hamilton Brown.1 Henry Whiteley, a visitor to Brown’s plantation in Jamaica, described the brutality of Harris’ ancestor in a pamphlet he wrote. He described the whipping of a slave owned by Brown thus:

What shall Vice President Harris do? Her proposals of reparations for slavery would place her in the position of both giving and receiving reparations. She might say: “I had nothing to do with Hamilton Brown’s ownership of slaves!” She is correct, of course. It might also be true that her genealogical relationship with Brown came about because Brown had an unwelcome relationship with a slave—further evidence that Kamala Harris is not responsible for the sins or crimes of her ancestors. This is an example of why a policy of reparations for actions committed by one’s ancestors is an unworkable concept. Looking toward Africa, we can ask about a young Hutu man whose family left Rwanda before the Hutus started slaughtering Tutsis. Is he responsible for the crimes of other Hutus? If ancestral and collective guilt is a valid reality, then it must be defined as a global reality. If any person is responsible for the crimes of their ancestors and their groups, then everyone is guilty because no one can state that their ancestors never did anything that was harmful to others. This applies across all groups, including the two major groups of humans: men and women. Not every man was an evil patriarch, and not every woman was innocent. At the level of the individual, harm and pain exist on both sides. This is not a popular view, and some women will be outraged that I might suggest this—as a man. But bear with me . . . Revenge for ancestral and group crimes is a lose-lose transaction. An eye for an eye really does make the whole world blind. What then can we do about the reality of the suffering in human history that has been inflicted upon the innocent by aggressors? Unless we all want to end up blind and dead, the best way to proceed is to support the healing and harmony of the entire human race. How can that healing take place? It is clear that we are not our ancestors. We have our own thoughts and beliefs. We’re responsible for our own actions. We cannot control or be responsible for the actions of others. However, if we admire the virtues of love and kindness, we should all be able to say that historical crimes against others should never have happened. Thus, we can feel compassion for the historical pain felt by everyone. We can and should learn from history—from the mistakes of our ancestors as well as their good, loving, and creative actions. It is entirely appropriate to feel sadness that our bad ancestors harmed others. It is perfectly fine to express sympathy and apology to the descendants of the victims harmed by our ancestors or by our groups. It is also vital to remember that many of our ancestors were admirable and virtuous people. The goodness that we see in the world today has developed based on the efforts of our ancestors. Let me repeat that:

Many people concerned with racial justice forget that large numbers of human beings of every race advanced civilization and brought goodness to the world throughout history. It is destructive to peace and the health of civilization to brand the good people of history as evil simply because of the color of their skin. We also cannot afford to throw historical people away because they didn’t live up to twenty-first-century standards. Would we have done things differently? It is easy to say yes, from our perspective today, but it is unrealistic to think so. It is hugely important for everyone to accept the truth that all of us have complex and very problematic ancestral histories. Essentially, we all have to apologize to each other for the long and bloody history of the human race. With the global acknowledgment that we all have faulty histories, humility can begin to flower, and with humility, forgiveness and love can grow. The only way to untangle the pain of history is for all of us to acknowledge that all of us have historical pain, and all of us need to forgive and love everyone. It is also profoundly obvious that all humans, of every race and both genders, need to mature in their capacity to love others, to understand and feel sensitive to others, and to respect the sacred, individual rights of others. I believe that the defining questions of the twenty-first century will include these:

If we are defined only by the sins of our historical and group identities, the game is over, and our century will inevitably be soaked in blood, much like the twentieth century and all the centuries that went before. I choose to believe instead that every individual was birthed by God as a sacred masterpiece who has a choice now to turn away from hatred, strife, and violence and support the healing of the human race. If we remember that every person was once a newborn infant who grasped his or her mother’s bosom with an innate desire for comfort, love, security, and peace, we may be able to look at each person with the long-range view and the higher view of the Divine.

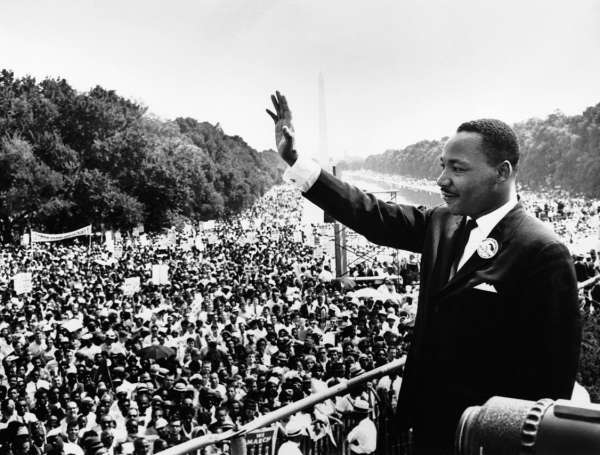

The healing of the human race requires an adjustment in the values of humanity. When love becomes the most valuable thing of all, then we do indeed have hope to abandon the revenge-driven tragedy of identity politics. We should not forget these timeless words by Dr. King:

We owe it to each other, and we owe it to ourselves to fulfill that very real and very practical dream.

Images: Painting: “Trade negotiations in the country of Eastern Slavs,” by Sergey Ivanov (1864–1910). 1909, Oil on cardboard, Height: 59.3 cm (23.3 ″); Width: 82 cm (32.2 ″). Public Domain Photo of Martin Luther King Jr., August 28, 1963, addressing crowd from Lincoln Memorial, Site of “I Have A Dream” speech, Public Domain, www.marines.mil/unit/mcasiwakuni/ Endnotes 1. “Kamala Harris’ Jamaican Heritage,” Jamaica Global, January 13, 2019, Updated January 14, 2019. Sub-article inserted in above: “Reflections of a Jamaican Father,” Donald J. Harris. https://archive.ph/907zm 2. Megan Fox, “Reparations Time? Kamala Harris’ Father Says Family Descended from a Jamaican Slave Owner,” February 22, 2019 Quote excerpted from Henry Whiteley’s pamphlet, “Three months in Jamaica in 1832, Comprising a Residence on a Sugar Plantation.” https://books.google.com/books?id=7uATZj4RrIUC&pg=PA5#v=onepage&q&f=false 3. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Strength to Love,” Chapter Five: “Loving Your Enemies.” page 47. Fortress Press Gift Edition 2010. 4. Martin Luther King, Jr. “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered August 28, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, DC https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm

Peter Falkenberg Brown is passionate about writing, publishing, public speaking and film. He hopes that someday he can live up to one of his favorite mottos: “Expressing God’s kind and compassionate love in all directions, every second of every day, creates an infinitely expanding sphere of heart.”

(Comments are moderated and must be approved.) “The Epiphany of Zebediah Clump”

Watch our first film right here. |